I want to invite you to read some words that may make you uncomfortable, and I encourage all of my readers to read, reflect, and keep an open mind. We often find our greatest opportunity for growth by stepping outside our realm of comfort and into an arena of discomfort. Use the movement from comfort to discomfort as an opportunity to understand how our identities lead to bias and create a lack of equity among our students.

As educators, our experiences shape biases and these biases can create disadvantages for students. The biases we carry can influence how we teach and respond to students. Likewise, how our students participate and engage with faculty and course content is influenced by their biases, experiences, and preconceived expectations of us and the course content.

The start of each semester presents me with an opportunity to remember that my students bring their own cultural and societal experiences and biases, impacting how they experience my courses. Cultural humility, which involves recognizing and reflecting on the difference between my own culture and identity and the cultures and identities of my students, requires ongoing reflection and growth on my part to understand who my students are. I have realized that in order to create a more equitable and inclusive classroom, where all students are valued and respected, I must practice cultural humility and acknowledge my students’ differences in race, ethnicity, class, sex and gender.

Why do the identities of students and instructor matter at all? The mistrust that underrepresented minority (URM) students have in white faculty has been building for decades due to personal experience, discrimination and mistrust within our medical and legal systems, and an increase in social justice unrest. The oppressive stresses felt by URM students in society are carried into the classroom and intensified when URM students see white professors as authoritarians.

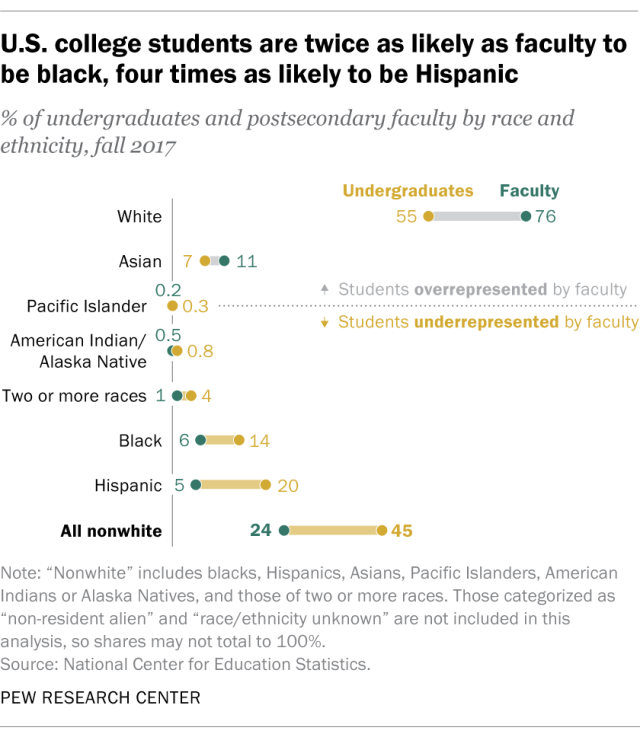

According to a 2017 Pew Research looking at college faculty and student diversity, 76.5% of all faculty that students encounter is white. Comparatively, according to the AACU, students of color enrolled in undergraduate education, in 2016, comprised 45.2 percent of our student population. At the graduate level, students of color represented 32.0 percent of enrollment. This means that only 23.5% of college professors represent communities of color.

To give an idea of how my institution compares to the research, during the 2019-2020 academic year 84.8% of the faculty identified white, compared to 8.9% of the faculty identified as Black and 4.3% of faculty identifying Hispanic. Our student body is 26% Hispanic, 17% Black, and 48% White. Our total population of students of color is 43% of the student body, but faculty they can identify with only make up 13.2%. URM students are enrolling in courses and being educated by professors who cannot empathize with or relate to social, family, and justice experiences. How does your institution compare with the data?

I believe that the biases brought to the classroom by URM students requires me to work harder to break down barriers of race, sex, and gender and establish trust with my students that allows for greater success and perseverance. The delay in establishing instructor-student trust relationships is sometimes the culprit behind the achievement gap seen at community colleges. In a report published in 2014 in the JSTOR, researchers found that the performance gap (withdrawal rate and grade performance) for students of color enrolled in courses taught by instructors of color was reduced by 20-50%.

This data is reinforced by my own experiences, and consequently, I owe it to my students to not be a gatekeeper of their education, to not subscribe to a fixed mindset. We must see our students’ color and attempt to unravel their biases; it is only in seeing color that we can start to understand their experiences, history, and biases that they bring to our classrooms.

What are some “quick to implement” strategies in building trust with your students? Here are changes that I have made to build relationships with my students.

- I start with my syllabus. It is the first introduction to me that students have. So consider: Is it inclusive? Is the syllabus written in a “negative” or “penalizing tone”? What support do you outline in your syllabus? Do you identify your pronouns after your name?

- I take risks. I inject personal stories of difficult periods of my journey and allow students to share their stories. I listen to and validate their stories. In doing so, I validate my student’s experiences. In becoming vulnerable, students will see you as being human and relatable to them.

- I am mindful of words spoken. I correct instances of microaggression within my classes. I also need admit when I misspeak or engage in microaggression-infused conversations, even with colleagues.

- I recognize my own privilege. I acknowledge it, and I use the acknowledgment to start discussions of race and sexuality within my courses. I allow students to express their experiences, encourage different views – made sure to allow and encourage ALL students to offer opinion, even if it had already been spoken.

- I am open about my support of students of color. I hang fliers on my office door that promote DEI events on my campus. I participated in Safe Zone training on my campus and display the insignia on my door, scanned it and put it in my syllabi, visually showing support with my words and action.

More specific ways to increase inclusiveness will be the topic of future blogs in this series.

We owe it to our students to be the best advocates for inclusive, equitable educational practices and for working collaboratively with peers to support greater diversity in our classrooms, departments, and fields of study. What challenges with developing cultural humility can you perceive? What changes can you make to your classroom to break down barriers caused by our different identities? What steps can you take in earning your students’ trust in order to transform their educational experience?

Larry Young is Professor of Biology and Anatomy & Physiology at Polk State College in central Florida. In addition to his teaching, Larry works with the colleges Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP) program as a research mentor and campus coordinator/club advisor. He earned his B.S. in Biology from Richard Stockton University, New Jersey in 2000 and his Masters in Life Science at the University of Maryland, College Park in 2008. His work in DEI education has led him to incorporate social justice relationships to A&P content taught within his courses. He also teaches Biology of Sexuality and Gender. When not teaching and hanging with HAPS humans you can find Larry, and his wife Niqui, paddle boarding in the Gulf of Mexico, enjoying the beach, working out, and when traveling, finding the local distilleries and breweries to enjoy the regional flavors, but also learn of the history, experiences, and diversity of communities brought together by some yeast, grains, and patience.

Larry Young is Professor of Biology and Anatomy & Physiology at Polk State College in central Florida. In addition to his teaching, Larry works with the colleges Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP) program as a research mentor and campus coordinator/club advisor. He earned his B.S. in Biology from Richard Stockton University, New Jersey in 2000 and his Masters in Life Science at the University of Maryland, College Park in 2008. His work in DEI education has led him to incorporate social justice relationships to A&P content taught within his courses. He also teaches Biology of Sexuality and Gender. When not teaching and hanging with HAPS humans you can find Larry, and his wife Niqui, paddle boarding in the Gulf of Mexico, enjoying the beach, working out, and when traveling, finding the local distilleries and breweries to enjoy the regional flavors, but also learn of the history, experiences, and diversity of communities brought together by some yeast, grains, and patience.

I enjoyed this blog and I will refer to it as I approach beginning another semester. Thanks for posting, Larry.

This is a great postt